|

||||||||||||

Bruno Schull's Letters From BarcelonaBruno Schull met Hiroshi Iimura while he was a Cal (U.C. Berkeley) student and local bike racer. For a few years he worked at Jitensha Studio. Later he married and moved to Barcelona and more recently to Basel, Switzerland. Every so often he sends us these letters, anecdotes of his experiences there. Bruno also is the author of a lovely book about cycling called the The Long Season, published by Breakaway Books, ISBN 1-891369-32-6. |

||||||||||||

|

The Collector, May 2013 | Ontogeny Recapitulates Phylogeny, May 2011 | Maurice de Vlaminck, May 2011 | Basel Stadt and Basel Land, Dec. 2009 | Confessions of a Schrader Man, Oct. 2009 | El Afilador, Jan. 2008 | The Postman, Oct. 2007 | Bicing, May 2007 | A Sailboat Becalmed, Jan. 2007

Les Alpes Vaudoises, Sept. 2006 | Basic Black Bike, August 2006 | Cap Problema, Je. 2006 | A Tale of Two Bicycles, Sept. 2005 | The West, Aug. 2005 | New Year Tune Up, Jan. 2005 Ciclo Bus, Dec. 2004 | Jazz, July 2004 | Borrowed Bicycle, Apr. 2004 | Today I Unpacked My Bicycle, Oct. 2003 |

||||||||||||

|

May, 2013

This is a story about collecting bicycles, and growing older, and remembering certain times and places, and how these feelings are filtered through physical objects and our surroundings. Yesterday, I bought a new bicycle. This apparently simple task was fraught with difficulty. First, I already had two bicycles, a city bike for riding to work, and a mountain bike for riding in the forest. So I did not really need a new bicycle. Buying a bicycle for no purpose other than to enjoy its ownership put me into a category I had thus far avoided in my life, despite my long affinity for cycling, that of a collector. I did not really want to become a bicycle collector; I just wanted a road bicycle to ride in the spring. But things quickly became complicated. What kind of bicycle would I buy? If I bought one bicycle would I buy another? How would I pay for them? Where would I keep them? And so on. As I considered these questions, I realized that I was actually searching for something very specific. First, I was not interested in a classic bicycle. I did not want a Masi made by Falerio, nor a Merckx made by De Rosa, nor a De Rosa for that matter, nor a silver Cinelli Supercorsa, nor a blue Gios Torino, nor a celeste Bianchi Specialissima. I did not want a Peugeot PX10, nor a Raleigh TI, nor a Rene Herse. I did not want a Serotta, nor a Richard Sachs, nor a Rainbow Trout. Instead, I wanted a simple lugged steel road bicycle. In particular, I wanted a bicycle from the late 1980’s or early 1990’s. The following characteristics will help define the appropriate period. After the Brooks saddles but before the Selle Italia Flite. After aerodynamic brake levers but before STI. After clinchers improved but before deep dish rims took over. If you were a cyclist during that period, the kind of bicycle I was looking for will be clear. To my mind, at that time, bicycles achieved a level of practicality, utility and elegance not seen today. In terms of craftsmanship, I was not looking for a custom made bicycle built by a master, nor was I looking for a mass produced machine assembled in a factory. I was looking for something made in the kind of small to medium size shop common in Italy, where several skilled artisans work together, each focusing on one task, to create a bicycle. The finished product is usually presentable but not perfect, beautiful but suitable for every day use. In terms of parts, I would search for Japanese components, to help keep the price down. Thankfully, such bicycles are plentiful in Basel. Cycling is popular here, and has been for quite some time, so there are many bicycles in circulation. People generally take care of things, so these bicycles survive intact. Finally, old bicycles have become popular with young people, for whom a vintage road machine confers a certain style. They discard dropped bars and gears in favor of flat bars and single speeds, and swoop through the streets on what they call “city flitzers” or city flyers. Many bicycles are left in original condition, and it’s always a surprise when I see somebody riding one, for example, a young women, perhaps twenty years old, pedaling with a particular silhouette, something about the large frame and low seat, hair streaming back, long legs driving the pedals, wearing a backpack and scarf, on her way to some errand about the city, looking every part like a female incarnation of Anquetil or Coppi, oblivious to how her bicycle places her in the world, at a particular point in time, for a brief moment. It’s beautiful to see, and fills me with emotions I can’t quite express. I began my search on a popular web site where people exchange goods and services. The bicycle pages typically contain over one hundred entries, and it was only a matter of time before I found something which fit my criteria. After one month of deliberation, I clicked the “buy” button on my computer. This virtual act set in motion a chain of real world events, whereby a recent immigrant from Kosovo, married to a woman from Germany, set off from nearby Zurich, with a bicycle designed in Switzerland and built in Italy, and arrived at my door, at which point I handed him the money, and retired to admire my new purchase. The actual brand was not important, but it might be interesting to note that the bicycle was a Sepp Fuchs, the eponymous brand of Josef “Sepp” Fuchs, a Swiss professional who raced in the 1970’s and 1980’s, mostly in support of well known riders such as Ocana, Saronni and Moser, although he won the Swiss national road championship twice, placed in the top ten of the Tour de Suisse, the Giro d’Italia and the Tour de France, and took Liege-Bastogne-Liege, his best victory, in 1981, after which he opened a small shop in Zurich, where he sold bicycles bearing his name, and was known as a friendly and accommodating patron, the kind of person who would lend you a tool if necessary, until the shop closed in 2009. It’s difficult to convey the pure joy that attends the acquisition of a new bicycle. The frame was perfect. It was made with Reynolds 531 tubing. The lugs and dropouts were clean. The seat cluster was attractive. It had regular brake cable routing and recessed brake bolts and a bolt on front derailleur. The fork had a flat crown and a natural curve. The finish work was good but not impeccable. The components were also perfect. Shimano 600 from the right period. Down tube shifters. Side pull brakes. Forged aluminum crank and tapered bottom bracket spindle. Handlebars with a round bend. Standard brake levers. Clincher tires. Toe clips. Everything was in good condition. In fact, it appeared brand new. I went for a ride. From my house, I climbed above the city, and came out on a broad level, where suburban homes share space with working farms, open fields, stands of trees, and light industry, interspersed with small winding roads. Following the roads, I began riding faster, until I disappeared into the country. It had been a long time since I rode a bicycle like that, tucked down in the drops, standing on the pedals, sweeping around the corners. It brought back a lot of memories from the time when I was twenty years old, and raced bicycles. So many hours on the road. So many races. So many moments of frustration and despair and longing and friendship and elation. I didn’t remember any race in particular, just the feeling of pushing myself hard, channeling my emotions through the bicycle, vehicle of self expression. When I was racing, I didn’t have a road bicycle like the one I bought. Bicycles had already begin their evolution toward what they are now. My racing bicycle had oversize tubes, TIG welded joints, a straight fork. Brakes and gears at my fingertips, Vento rims, Time pedals. It was lighter, stiffer, stronger, more durable. It was faster—if you can apply that word to a bicycle. But it did not have the same feel. I try not to be superstitious about bicycle feel, but we are all entitled to our strange beliefs. For example, one famous builder believed that position was optimal when the inner ear was aligned with the steering axis. My own belief is that lugged steel bicycles resonate like a tuning fork, humming and singing along the road, in a way that no other material can match. As I rode through the country, I could feel the bicycle moving beneath me, bending and flexing and springing, almost alive, unmistakable and wonderful. Something else made the bicycle fun. Modern bicycles function so well that they practically disappear beneath you, but my bicycle required attention. I needed to shift my body over the bumps. I needed to apply the brakes gently. I needed to reach down to trim the derailleurs. This is part of the attraction of old technology; it demands a certain level of technique. The analogies are numerous and have been made before—taking pictures with manual cameras, listening to music with analog audio equipment. I don’t know enough about these fields to offer insight, but I can say that my bicycle engendered a heightened awareness, a deeper involvement, which served to draw me further into the ride, the surroundings, and perhaps myself. As I started home, I reached a small town outside Basel, and decided to climb one more hill. That’s how my bicycle made me feel—I wanted to keep going. I rode through a small square, across tram tracks set in pavement, careful of the narrow tires in the deep grooves, past a fountain, where a bronze dragon poured a stream of water from its mouth into a white stone basin, and a cafe, where people sat in the warm sun, sampling espresso and croissants, or beer and sandwiches, and then I turned onto the climb, and rode past the post office, closed for the afternoon, with the sign of the post horn hanging above the door, and past old buildings with white stucco and wood timber facades and window boxes of bright red flowers, and past farm buildings and yards tracked with mud, and then the road went up along a stone wall, and passed beneath some trees, and came out into the open, where there were more farms, and more fields, rectangles of brown earth, squares of green, swaths of yellow flowers, rolling toward forest in the distance. When the climb leveled, I turned onto a dirt road, a way I had never gone before, and rode through an orchard, following a line of trees, decorated with small white blossoms. As I rode through the orchard, I thought once again, that the area around Basel, the small corner where Switzerland, Germany and France come together in the Alsace, is an unrecognized cycling paradise. What luck, I thought, to have landed here, quite by accident, at this time in my life. The road ended above a new housing development, and I looked down over Basel, with the spires from the cathedrals, and the towers from the factories, and the many bridges crossing the faint glint of the Rhine. Then I joined a road I knew, and went down a steep rushing descent, pedaling along quiet streets to my home. My first ride was over. Now the real work would start. I would probably have the frame repainted. I would need a longer stem and wider bars. Likewise I would need longer cranks and larger tires and platform pedals. I would probably change other parts as well, but I would try to remember my original purpose: I want a bicycle that I can ride, even if that means mixing parts or making concessions that a real collector might not approve. And that, I guess, is the pleasure and work of being a collector. To take something old and make it new. To transform a physical object into a vehicle for memories and emotions. To find a place in the world of bicycles.

|

||||||||||||

May, 2011

Ontogeny Recapitulates PhylogenyLast week, my wife and I enjoyed an important landmark: we bought our daughter her first bicycle! Let me qualify that: it is not really a bicycle, but rather a kind of push-bicycle, propelled by swinging the legs along the ground, of the kind popular in Switzerland, said to help children gain a greater sense of balance, before they graduate to true bicycles. I don't know if these vehicles actually help children learn how to ride, but I can tell you that my daughter loves her bicycle. She calls it her “velo” from her mother tongue, French, and my wife and I can no longer leave our house without entertaining the important question of how the velo fits into our plans. The bicycle is a little too big for my daughter right now, but she enjoys simply steering it around, like a companion. Walks around the neighborhood have become serious affairs, during which she intently pushes the bicycle along the sidewalk, up and down curbs, and so on, periodically demanding to go “fast,” at which point she climbs onto the seat, and her father is required to lean over, in a sort of a crouch, and run at breakneck speeds, while she laughs with delight. So. My daughter has started down the long road of cycling pleasure. That makes me smile. But what, if anything, could this possibly have to do with strange title of this post? I am a biology teacher, and, not surprisingly, biology often pervades my thoughts. Thus, while watching my daughter on her new bicycle, I am reminded an old idea. The phrase “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” is an expression of a theory known as recapitulation. This theory originated in the fertile minds of the German natural philosophers, in the 1790's, and was formally proposed by a French physician, with the regal name of Antoine Etienne Renaud Augustin Serres, in the 1820's. It was later adopted by the eminent German biologist, Ernst Haeckel, in 1866, who coined the aforementioned phrase, and produced the extraordinary and beautiful, Kunstformen der Natur, or Artforms in Nature, a set of drawings which depicts in great detail and often vivid color the diversity of life on Earth. Roughly, the theory unites the fields of embryology (ontogeny) and evolution (phylogeny), proposing that a developing fetus passes through a series of intermediate stages, each of which replicates, or recapitulates, the characteristics of ancestral forms. Therefore, the embryos of mammals may pass through a stage where they appear to have gills, or something like gills, reflecting, in their development, the evolution of mammals from fish. Numerous additional examples can be found, and the theory enjoyed broad support, before it was rigorously tested, and eventually discarded, by the start of the Twentieth Century. Recapitulation is perhaps best understood, not as a strict biological law, but rather as a set of observations about a limited number of species, which provide some insight into our descent from common ancestors, and the unity of life. Scientific validity notwithstanding, recapitulation is an interesting idea, and it's always fun to try to find examples of this kind of thing in the world. When I see my daughter on her bicycle, I think of the German Baron Karl Fredreich Drais or the French Compte de Sivrac, propelling their early bicycles by swinging their legs. And when I think of tricycles, perhaps the first true pedal-powered vehicles that many children ride, I see echoes of velocipedes and high-wheeled ordinaries-the next step in bicycle evolution. In the same loose way that development may reflect evolution in biology, the progression from children's push bicycles, to simple pedal bicycles, through various iterations with increasing numbers of gears, more complexity, and so on, before the emergence of an adult bicycles, in some way reflects the development of the bicycle itself. Stated explicitly, this is a trivial idea, with various counter examples, and bewildering side branches, which can not be neatly accommodated, like the diversity of life. But it makes the mind hum. It is natural to look for patterns in the world. As a renowned professor I was lucky to encounter in college once said, “Our brains are in the business of taking things apart and putting them back together.” Thus, in many ways, when I ride-or watch my daughter ride — I think. And this, more than anything else, is the true pleasure of bicycling, which I hope my daughter will enjoy in the future. As a side note, the bicycle we bought is the Jumper produced by the German company, Like a Bike. It has an aluminum frame, a straight blade fork, a quick release seat post, a single pivot suspension with an elastomer shock absorber, radial spoke wheels, aluminum rims, and Schwalbe puncture resistant tires, remarkable specifications for a children's bicycle! The attached pictures show a popular progression, from bicycle trailer, through two types of tandem carrier, including the “Follow Me,” to a true bicycle, fully outfitted, as befitting any European commuter, with a fenders, front bag, rack, light, bell, and helmet.

|

||||||||||||

May, 2011

Maurice de VlaminckAt the turn of the nineteenth century, the prevailing style of painting in France, characterized by pastoral landscapes and natural representation, was overturned by a wild new movement, called Fauvism, which employed bright colors and bold emotive strokes. Championed by a younger generation of artists, including Andre Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, this movement set the tone for much modern art that followed. Vlaminck is generally considered the father of Fauvism. What is less well known is that Vlaminck was a bicycle racer. Vlaminck was born in Paris, 1876. Both parents were musicians, and he developed an early aptitude for music, which later proved invaluable. His childhood was spent in the city and suburbs, which he explored by bicycle. In his memoir, A Dangerous Corner, Vlaminck remembered, “For me, the discovery of the outside world dates from my acquisition of a bicycle, I spent whole days on the high-road. I rode through villages, towns and countryside. I tasted dust; rain poured down on me; I struggled against the wind. With my cycle I was able to visit places I never dreamed of... It is to the bicycle that I owe my first love of the open air, space and liberty... I rode easily, without ever getting tired, a hundred or two hundred kilometers a day on poetic excursions.” When he was a young man, Vlaminck began bicycle racing. He entered several local races with great success, and trained on the Buffalo cycling track in Paris. Of his early education on the track, he wrote, “I got to know other men. I learned to measure up my fellow competitors of the track, to size up their muscles and breadth of shoulders, to note their pedal action and evaluate their intelligence. Contrary to the bourgeois, who judges a man by his social position and how much money he possesses, I have always weighed up a man according to his intrinsic worth.” Vlaminck specialized in racing through the provinces, traversing Chatou, Seine, Harve, Mantes, Rouen, Bordeaux and Tours. These were long races of two or three hundred kilometers, which sometimes lasted all day and night, “Battling...elbow to elbow, carefully watching ones opponent, hoping or guessing how tired or dejected he might be, watching the effort of pedaling and looking out for cramp-cramp so familiar to hardened track riders, cramp that comes with the cold at the break of dawn when one has been riding all night...round and round on the concrete track; the riders' dressing rooms, suffocatingly hot and filled with conflicting odors—of rubber tyres warmed by the sun through the pine planks which, in turn, gave off a smell of resin; the mouldy stench of camphorated oil, embrocation, petrol and sweaty jerseys and shorts-this was the milieu I loved.” In 1896, Vlaminck was selected to ride the prestigious Grand Prix de Paris, but he fell sick, and was forced to withdraw from the race. When he recovered his health, he left Paris to perform his military service. In the army, Vlaminck first employed his musical talents, playing the double-bass in the regimental band, a job which distracted him from the monotony of military life. When Vlaminck was discharged, he continued to play music, supporting himself by providing violin and trumpet lessons to willing students. He also befriended several prominent figures, including Faure, Malato, Libertad, Almereyda, Tailhade, Pioch and the socialist Zola. Vlaminck attended functions organized by these figures, and wrote articles for revolutionary newspapers, such as Fin de Siecle and La Libertaire, however, he was too independent to associate himself with any one movement. By night he played in underground cabarets and bohemian night clubs, and by day painted portraits and scenes along the Seine. During this period, Vlaminck seems to have been something of a lost soul. Francis Carco, a close friend, remembered, “Vlaminck, the disreputable-looking habitué of suburban inns, pipe in mouth, with his bicycle, his polo-neck jersey...” Vlaminck recounts how he finally left Paris without, “enough pennies to pay for the tram.” He wandered through the provinces where he once raced his bicycle, “under an angry sky, the Seine overflowed its banks...all seemed to be overshadowed by a desolate sadness.” That was when Vlaminck began to paint seriously. “I wanted to employ my muscles and mind and to live in a quite different way,” he wrote. “I felt a strong combative urge, but it was to gain a less easy and less tangible victory over a completely abstract adversary.” With Andre Derain, whom he met by chance on a train, Vlaminck founded the school of Chatou, and the two began working in an old restaurant, frequenting the neighboring cafe, and taking long walks together through the countryside. His freedom, he believed, allowed him to, “take all sorts of liberties...I felt a tremendous urge to recreate a new world seen through my own eyes, a world which was entirely mine...I realized that all I wanted to do was to find a new and profound way of identifying myself with the soil... I decided just as if I were directing my orchestra, in order to make myself heard to use only the brasses, cymbals, and the bass drum, which in this case were tubes of color... I highlighted all my tone values and transposed into an orchestration of pure color every single thing I felt. I was a tender barbarian... I squeezed tubes of paint onto my canvas, and used only vermilions, chromes, and greens, and Prussian blues to scream what I wanted to say.” Fauvism was born. The new paintings were immersed with color. Reds and pinks, yellows and greens, blues and purples. They did not attempt to portray reality directly; rather, they communicated feelings, and in this way captured reality more effectively than purely representational art. Moreover, they were vibrant and intense. As Vlaminck once said to Seurat, “lets go intoxicate ourselves with light once again.” The paintings were considered shocking, even scandalous, and Vlaminck and Derain were labeled Les Grands Fauve, the great wild men. Later, their brilliance was recognized. When Vlaminck was established, he moved his wife and daughters to the countryside, and settled into a comfortable routine, producing numerous oil paintings, water colors, pencil drawings, woodcuts and lithographs. These works portray fields and forest, farmhouses and windmills, towns and churches, the sun and sky. The perspective is unique. Any student of Vlaminck who is a bicycle rider, cannot fail to see the influence of his early passion on his later painting. For example, one of Vlaminck's favorite subjects was the road. In many paintings, roads dominate the scene, unrolling as from beneath a bicycle wheel, extending into the distance. In fact, the title of one of Vlaminck's most famous paintings is The Road. Art critic Jean Selz explains, “Roads always held a great fascination for him, and they played an important part in his work as they did in his life... The road had also been his livelihood, for he had been a professional racing-cyclist. Then, the pleasure of contemplation had been replaced by the heat of competition and the determination to devour a stretch of road with a pair of wheels...flashing through the countryside became a violent confrontation...with the road charging triumphantly through the lot.” Vlaminck described his fascination, “An open stretch of country, a man walking along the road, the face of a town, the walls of a factory, the somber outline of a forest, suggest, for certain inscrutable reasons, hopes and fears which, in the very speed at which they follow one another, become fused into obscure presentiments that give birth to dreams.” It was on a bicycle, then, that Vlaminck dreamed. To the bicycle he owed his love of nature, freedom, independence, and the inspiration that made him an artist. And he never forgot this debt. Describing his youth as a bicycle racer, Vlaminck wrote, “The strongest emotions I have experienced were a result of those days...never, anywhere, have I felt such utter and complete satisfaction as I did...when I was nothing more than the winner of a simple bicycle race.”

|

||||||||||||

Basel Stadt and Basel LandEntirely by accident, and completely to my surprise, I find myself living in one of the bicycle capitals of the world. When you think of bike friendly cities, you imagine pedaling along a canal in Amsterdam, riding down a path in Portland, or touring the sights in Paris, where, for the last several years, the public has enjoyed the wildly popular Velib bicycle sharing program. But not Basel, Switzerland. In the land of snowy peaks, noisy clocks and timely trains, Basel is known for its medieval buildings and pharmaceutical companies, crowded along the banks of the Rhine, not for progressive transportation. And yet, Basel enjoys a vibrant cycling culture, which rivals that of many European cities. To convey the bicycling culture in Basel, I have to tell a story in two parts: Basel Stadt and Basel Land. This reflects neighboring regions, city and country, which present distinct cycling charms. The first part of my story involves Basel Stadt. Consider the following statistics: in the United States, approximately 1% of all trips are made on bicycles. Similar numbers are found in the United Kingdom and Australia. In Europe, numbers are generally higher: France and Italy 3%, Germany 10%, the Netherlands 27%. In some European cities, bicycle use exceeds other forms of transportation, for example, Copenhagen, where more than 40% of all trips are made on bicycles. In Basel, more than 20% of all trips are made on bicycles, not as many as Copenhagen, though well above the Swiss national average of 6%. What makes cycling so popular in Basel? Bicycle infrastructure plays an important role. Some features which cyclists in Basel enjoy include: designated lanes and traffic signals, ample street parking, protected indoor storage, accessible public rental, narrow ramps on stairs, vending machines for inner tubes, and extensive marked routes. While I am impressed by these measures, I am more interested in bicycle diversity. In biology, diversity may be characterized by two factors: the total number of living things, or abundance, and the number of different kinds of living things, or richness. Bicycle diversity may be analyzed in a similar fashion. Bicycle abundance is certainly high in Basel. Bicycles crowd the streets and compete for space with cars and trams. Bicycles fill parking spots and overflow onto sidewalks. Every neighborhood has its own bicycle shop, including Velo Plus, distinguished by knowledgeable staff, quality products and a professional work station for customers, as well as the astounding fact that the shop does not sell bicycles, but only components. If such a shop exists, it stands to reason, there must be many bicycles in the city. Bicycle richness is also high in Basel. I have counted every conceivable type of machine, and all variations thereof, including road bikes and mountain bikes, touring bikes and cyclecross bikes, track bikes and time trial bikes, commuting bikes and cargo bikes, folding bikes, electric bikes, vintage bikes, modern bikes and so on. This diversity, of course, supports a corresponding diversity of riders. It seems superfluous to state that all kinds of people ride bicycles in Basel. One phenomenon which illustrates this point is the cycling family. Parents often ride with children, who follow an established progression: infants are towed in trailers, toddlers are packaged into seats, beginners balance on training devices, and youngsters follow on first bicycles. Bicycles are part of Basel Stadt. And, unlike many other aspects of Swiss culture, cycling is accessible to everybody. The best way to participate is to rent a bicycle. Wind through the medieval streets. Cross the Rhine on an old bridge. Stop for a break in a quiet park. You will have plenty of company on two wheels. The second part of my story begins with a simple assertion: I am convinced that Basel Land is a bicycling touring paradise. Perhaps this is not surprising: Basel Land is nestled between France, the literal if not spiritual home of randonnee cycling, the Black Forest, in Germany, whose tranquil beauty inspired Goethe and Thomas Mann, the Alsace, along the Rhine, where vineyards climb green slopes, and the Jura mountains, folded valleys and ridges, which harbor the birthplace of the mysterious elixir, absinthe. From my home in the neighborhood of Neubad, nestled on the border between city and country, I ride precisely one half block, before picking up a small path, covered with trees, which leads to the edge of the local forest. There, a network of roads and trails spreads out into Basel Land. The country is composed of gentle rolling hills, never steep though never flat. The hills are covered with a patchwork of forest and farmland. Sometimes the roads wind through woods, and sometimes they cut across open fields. Occasionally, you encounter vehicles, but for the most part your only companions are runners, walkers, horse riders and other cyclists. Despite the fact that you are in the country the land is developed. The roads are maintained and the trails are swept clean. The crops are cleared and the ground is tilled. The forests are harvested and the fresh timber is stacked in neat piles. Signs provide directions, and benches are positioned to take in pleasing views. With a sturdy touring bicycle and a good map, you could ride for weeks through Basel Land without covering the same ground twice. And at any point, if you wished, you could simply ride to the nearest town and enjoy restaurants, hotels and local hospitality. You could even board a train and return to your starting point—all of the trains have bicycle cars. To conclude, Basel Land and Basel Stadt comprise a wonderful bicycling habitat. Bicycles are woven into the culture at many levels, and are an integral part of life. Browse the photos below to sample the sights. Then visit, and discover the truth that while a picture may be worth a thousand words, a bicycle ride is worth a thousand more. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

October, 2009

Confessions of a Schrader ManI have a confession to make: I ride a bicycle with Schrader valves. I don’t mean that I have some kind of city bicycle or second bicycle with Schrader valves. My bicycle—the one that I ride on roads and trails, the one upon which I lavish my affections—has Schrader valves. At one point in my life, ten or fifteen years ago perhaps, this confession would have caused me great shame. You see, I was a bike racer, that species of obsessed Europhile, who trims all extraneous weight from their bicycle, wears tight shorts, shaves their legs, and in all other respects imitates their counterparts on the continent. Viewed in this light, Schrader valves represent, at the very least, a few grams of extra mass, at most an unacceptable break with tradition; racing bicycles do not have Schrader valves. Like many bike racers, I also worked in a bicycle shop, assembling expensive machines for devoted attendees. Thus, I was initiated into the arcane rituals of bicycle aesthetes. Brake cables had to be trimmed to perfection, quick release levers had to be closed correctly, even tires had to be mounted in a specific manner. In such a world, riding a bicycle with Schrader valves was nothing less than sacrilegious, an almost incomprehensible act, like riding naked. The alternative, of course, is the presta valve. While Schrader valves are short and squat, presta valves are long and elegant. While Schrader valves are covered in dull black rubber, presta valves are constructed from gleaming metal. While Schrader valves are found on automobiles, tractors, wheelbarrows and other common vehicles, presta valves are found exclusively on bicycles. Most of all, presta valves are distinctly European, and lend bicycles a cosmopolitan allure. Looking back, across many intervening years, I can admit to certain undeniable truths about presta valves. First, they are difficult to inflate. Anybody who rode bicycles in the Nineteen Eighties will remember the ubiquitous plastic frame pumps produced by the Italian company Silca. After wrestling the cheap plastic head onto the presta valve, holding it awkwardly in place with one hand, you depressed the flimsy piston, at which point the handle slid inexorably backward, propelled by the pressure of the tire, producing the ominous sensation that the entire apparatus might explode in your hands. Has there ever been a pump which inflated presta valves efficiently? There was one: it was made by the French company Zefal, called the HPX, a nondescript black tool, as uninspiring as it was functional, which, unfortunately, suffered from the fact that the small lock ring on the handle had the noisome habit of rattling against your frame, disturbing even the most tranquil ride. Purists will speak of the technical superiority of the presta valve. Others will insist that the solution is the floor pump, such as the Silca track pump, famously made of chromoly steel, like the best bicycle frames, with a polished wood handle and a heavy brass head. The Silca track pump was no more practical than its plastic relative: it still required complex machinations to hold the head in place, and more often than not, vigorous efforts to inflate tires were met by a long hiss of escaping air. The fact that remains that presta valves are difficult to inflate. Schrader valves, in contrast, suffer no such difficulties. Because they are covered in rubber, pump heads form a tight seal. Because they are found on a wide variety of machines, it is not necessary to search for Italian or French pumps; you simply ride to the nearest gas station and inflate your tires with a compressor, the same way that you would with a car. The Schrader valve is simple and purposeful. The Schrader valve is for everybody. The Schrader valve is democratic. If my appreciation for Schrader valves is not enough, I have another confession to make: I ride with baggy shorts. Granted, now I am riding a mountain bike, on which breaches with fashion are tolerable, but riding with baggy shorts is the ultimate sin for which there is only one punishment: excommunication. If you ride with baggy shorts you are not a real cyclist. And yet. My baggy shorts are comfortable. Although I feared that they would bunch around my legs and flap in the wind, no such problems occur. Wearing baggy bicycle shorts is much like wearing regular clothing, which is to say, they simply disappear. As an added benefit, I can stop during rides, perform errands, and generally navigate the world, without looking like a circus performer in Lycra shorts. Last, but not least, I must confess that I ride my bicycle with sneakers. Anybody who has read this far will not be surprised by my astounding admission. What about cycling shoes? What about plastic cleats? What about energy loss and efficiency? Surely it is not enough to simply push down on the pedals; you must deliver power on the upstroke, the backstroke and so on, maneuvers only possible with modern cycling equipment. In truth, when I ride, I am no longer training. I do not do intervals, time trials or top speed sprints. I ride at a pace dictated by the feelings in my body. For this kind of exercise, sneakers suffice. Many cyclists secretly formulate their own eccentric theories, and I plead guilty to this accusation. My idea is that by riding with soft sneakers, instead of hard cycling shoes, I avoid the repetitive soft tissue injuries which plagued my former life. So that’s how I ride. With Schrader valves, baggy shorts and sneakers. The changes in the bicycle world over the last decade, a virtual Cambrian explosion of frame designs, riding styles, clothes and accessories, starting with suspended mountain bicycles and extending through fixed gear machines, cruisers and single speeds, has to a large extent rendered questions of style moot. And yet I still wonder about my personal evolution from bicycle racer to everyday rider. Is this growing up? Is it growing old? I am comforted my two observations. First, I am having fun. On most rides, I smile a great deal, if only inwardly. And when I return to my family, my wife and baby daughter, my daily concerns have for the most part disappeared, and that smile turns outward on those I love. Second, I am still a bicycle racer at heart. On every ride, if only for a moment, there is a point where I push myself to ride fast. Snaking through a forest on a winding trail, the trees blur on the sides, and my field of view narrow into a tunnel. I arrive at that faint edge, where every slight shift of weight and movement of the handlebars counts, close to the limits of body and mind. And at that point, it does not matter if am riding with Schrader valves. |

||||||||||||

January, 2008

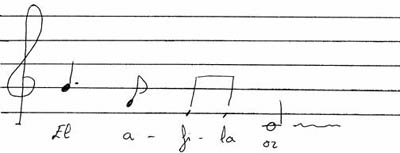

El AfiladorWhat sights and sounds characterize Barcelona? Sights are easy: the surreal spires of the Sagrada Familia, the cathedral in the Barri Gotic, the crowds on Las Ramblas. Sounds are more difficult. The fluid syllables of Catalan? The classic rhythm of the Sardana? The revving engine of a scooter? When I moved to Barcelona, I was mystified by a particular sound. Discovering the source of this sound became an adventure. And when I was finally successful, I was surprised to learn that the sound involved a bicycle. Morning. Laura and I wake to the clanging metal gate in the elevator, as the elderly woman who lives on the top floor of our building descends to walk her dog. As she exits the elevator, we are greeted by the sound of her voice, low and garrulous, and the barks of her dog, high and shrill, echoing in the hall. The front door creaks opens and swings closed with a resolute bang, which shakes the building. The day has begun. As Laura and I prepare breakfast, the street sounds intensify. Traffic passes in waves on Avenida Parralel, the truck driver who lives next door starts his vehicle, and the first police car rushes past, siren wailing. By the time I sit down in front of my computer, the sounds have changed. The elevator has stopped its ceaseless coming and going, and there are less cars on the avenue. Most people are at work. Now there are the sounds of delivery trucks, workers calling back and forth, and occasional fragments of conversation. Then I hear the sound, several high notes, like the call of a strange bird. The sound appears close, just beyond the window. I open the doors and step onto the balcony. Leaning over the railing, I scan the street. I see nothing out of the ordinary, just the small vegetable market, the grocery store, and two old women, returning from shopping, talking on the corner. There is only the sound. Eventually the sound disappears, only to return several days later, when least expected. One morning, I set out to follow the sound. Leaving our building, I walked in the direction of the sound. The sound traveled through the neighborhood, moving toward Montjuch Park, making a circle around the St. Antoni market, returning along the Avenida Mistral. Always the sound remained just ahead, traveling faster than I could walk. Finally, the sound lost itself in heavy traffic on Gran Via. I returned home. The mystery remained. The next time I heard the sound, I resolved to settle the matter. This time, I set out on bicycle. As before, the sound traced a circumlocutous path through the neighborhood. But I gained on the sound. Each time I heard the sound, I changed direction, pedaling furiously down the streets. Finally, I rounded a corner and found another man on a bicycle. The man was riding slowly on the sidewalk. Periodically, he raised his hand and produced the notes with a curious plastic flute. On the rear rack was a small metal box. From the handlebar hung a red plastic bucket filled with assorted objects. Fixed to the top tube was a makeshift grinding wheel. The man was a knife sharpener. El Afilador. I caught the knife sharpener. He was a young man, perhaps forty years old, with a full head of black hair, and a friendly manner. I asked him if he made house calls (he did). I told him our address (Calle Floridablanca). I set a date and time (the following day at noon). At the appointed hour, I was waiting outside our building holding two kitchen knives. The knife sharpener arrived promptly and set to work. First, he folded a large kickstand into a stable position, so that the rear wheel was supported off the ground. Then he stretched a long rubber band around the grinding wheel. The rubber band turned on a small steel rim fixed to the rear wheel. Finally, he mounted the bicycle and started pedaling. It was an old mountain bicycle, and many of the components were not maintained, but it worked. The grinding wheel began to whir. The grinding wheel had two stones: coarse and fine. The knife sharpener alternated between the two, shaping the blade and honing the edge. Every time he touched metal to stone, the sound changed, and sparks jumped from the wheel. When he finished sharpening the first blade, he placed the knife in a simple rack on the handlebar, and began sharpening the second. As he worked, he talked. He told me that he learned his trade from his father. His father used to work in the country outside Barcelona, sometimes riding for hours between small towns, sharpening ploughshares, shovels, axes and other farm implements. Later, when his father moved to the city, he began sharpening knives for restaurants, bars and anybody who answered the call of the flute. The flute was called a chiflo, a sort of Pan pipe, several tubes of descending length, each of which produced a different note. An ancient folk instrument, the ancestor of the harmonica and the pipe organ, the chiflo was traditionally carved from a solid block of wood, sometimes in the shape of a horse’s head. Later, the chiflo was made of plastic, readily available in toy stores for one peseta. Popular among children, the chiflo is the instrument of knife sharpeners throughout Spain. In fact, the sound is called, “La llamada del Afilador” (The Call of the Knife Sharpener). When the knife sharpener was done working with the grinding wheel, he dismounted, opened the metal box, selected a hand file, and made several quick passes over the knives. Then he wiped the knives clean with a rag from the plastic bucket, and passed them to me handle-first. I paid the knife sharpener. He closed the metal box, removed the rubber band, and folded the kickstand. Then he mounted the bicycle and disappeared around the corner. A few moments later, I heard the sound of the chiflo. This service cost me five Euros. In return, I received two very sharp kitchen knives. I also received a sharper understanding of the contrasts in Barcelona. On one hand, are the Sagrada Familia, the cathedral in the Barri Gotic and Las Ramblas. On the other hand, are the Forum and the Fira, convention centers for business, telecommunications and fashion events. On one hand, are traditions like Catalan and the Sardana. On the other hand, are immigrants from every corner of the globe, and dozens of new languages. On one hand, the currency of Barcelona is the Euro. On the other hand, many people in the city still think in pesetas. It seems impossible to imagine that in Barcelona, racing toward globalization, there is still a niche for a pedal-powered knife sharpener. And yet, this is precisely what makes the city fascinating. Barcelona is characterized by el afilador. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

The PostmanThis is a short story. The main character rides a bicycle, but, like the best bicycle stories, it is not only about bicycle riding. I do not remember where I learned about the story first. I either heard it on the street in Barcelona, Spain, or read it in a book in Berkeley, California, or saw it in a movie in New York City. But that does not matter. I suspect that wherever the story originated, it has been passed down, from person to person, bicyclist to bicyclist. It's a good story. The story involves a small town, somewhere in the United Kingdom. I imagine a town in Scotland, old gray houses set on a hill, narrow lanes, a church and square, and perhaps a brick factory—now closed—on the outskirts, bare fields and rolling green hills spreading away toward distant lakes and rocky peaks. In the town, of course, is a pub, on one of the narrow lanes, at the top of the hill. The pub has a Scottish name that invokes the Vikings and the Celtics, Inverness or Galloway or Glen Mhor, probably painted on a swinging wooden sign hanging above the door. Inside, the pub is dark, paneled in wood, with a damp musty smell, that only disappears when the fire is lit in the hearth, something which occurs only on the coldest days in winter. But, nonetheless, the pub is usually crowded, especially on Friday and Saturday nights, when the room is filled with the laughter and loud conversation of locals, the pub too far from the center of town for tourists to reach from the train station. Most Friday nights a man visits the pub. He is the postman, who still makes his rounds on an old upright bicycle, a Raleigh or Windsor, with a generator light, steel rod brakes, and heavy canvas mail bags front and rear, which are sometimes not empty when the postman leans the bicycle against the wall under the swinging wooden sign and enters the pub. The mail will not be delivered until Monday. The postman spends a good deal of time at the pub, knows most of the people, and sometimes eats dinner at the bar, empty pint glasses mounting beside empty plates. After several pints of ale, and perhaps a whiskey, on special occasions, he bids farewell to his friends, and makes his way outside, where he finds his bicycle waiting in the dark. That is when the story begins. The postman mounts the bicycle. Swinging his leg over the leather saddle, sometimes awkward when the mail bags are full, the postman pushes off and starts down the lane. He lives on the other side of the town, beside the old factory, where he used to work, before it closed. The lane is steep, and the surface is paved with heavy cobbled stones. The cobbles are slick with moisture and shine in the light from the windows. At the bottom of the lane the streets are covered by thick white mist which descends over the town at night. The postman weaves back and forth and begins to coast down the hill. He can feel the rough shuddering of the cobbles through the handlebars and the swinging of the mail bags and the pressure behind his eyes from the noise and smoke in the pub. He picks up speed, and the generator light begins to hum, casting a faint yellow circle onto the cobbles. At some point, the shuddering smoothes into a steady vibration, and he feels cool moisture against his face and wind moving through his hair and his head cleared by the fresh night air. Midway down the hill, the postman picks up speed, and touches the brakes. The stiff rods press against the heavy rims, and water streams from the wheels and soaks his pant legs. The bicycle slows and the generator light fades. The postman releases the brakes and the bicycle moves faster and once more the generator light casts a yellow circle on the cobbles. This process is repeated. The postman brakes, the bicycle slows, and the generator light wanes. The postman releases the brakes, the bicycle moves faster, and the generator light glows brightly. This is the most important part of the story. The postman needs to ride slow enough so that he does not fall, but fast enough so that the generator light will illuminate his path. At that moment, warmed by the company of friends, resonating with the rush of speed, he feels suddenly alive. The tires float over the cobbles, the water streams from the rims, the generator light hums, and the wind rushes against his face. The postman continues down the hill and disappears into the mist. That is the story. It does not matter weather or not you remember the details, but I hope you remember the important part. Who knows? Perhaps I did not remember it correctly. But you can tell the same story in any number ways. I like to remember the postman, balancing on the bicycle, suddenly alive. |

||||||||||||

May, 2007

BicingRegular readers may remember Ciclo Bus, or bicycle bus, a mobile bicycle rental network which Barcelona initiated several years ago (see December 2004). This spring, Barcelona launched a new bicycle-based, urban transportation solution, called Bicing. Bicing consists of a system of over one-thousand bicycles distributed at parking points throughout the city. At each parking point, there is a fleet of bicycles and a special rack. First you must become a registered user. Registration costs about forty dollars. When you register, you receive a magnetic card similar to a credit card. To use a bicycle, you swipe your card at a parking point, and a bicycle is automatically unlocked from the rack. The first thirty minutes are free. After thirty minutes, you pay about one dollar per hour. You may return the bicycle to any parking point around the city. The system seems to be very successful. Popular parking points often run out of bicycles! Check out the pictures of the Bicing system. Noteworthy details include the sleek wheel covers, the internal three-speed hubs, the integral front and rear lights activated by automatic light detectors, the chrome-plated front luggage racks which double as locks, the rack at the parking point, and the numbered bays for each bicycle. Come to Barcelona and go Bicing! |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

January, 2007

A Sailboat BecalmedThe holidays are over. After the New Year, most people return to work, to school, to their normal lives. Here, in Barcelona, Spain, this return is postponed. January 5th marks a holiday called Los Reyes, or, "The Kings," on which the Three Kings, or the Three Wise Men of the New Testament, arrive by boat at the port, and tour the city in a fantastic parade, complete with troupes of dancers, musicians, mechanical elephants and camels, the kings themselves, transported in carriages, and finally, bringing up the rear, a truck loaded with coal, surrounded by smoke and fireworks, a reminder of the devil on a night which celebrates the birth of the baby Jesus. The morning after the parade, the city is deserted, the crowds from the night before hidden in homes, where children eagerly unwrap presents, which are delivered on this day, and not Christmas day, as is customary in the United States. That morning, I stood at the window of my apartment, looking over the quiet streets, thinking not of the presents which I received on Christmas, but of a gift which I gave somebody for Los Reyes. A few days earlier, as I was walking to work, surrounded by the usual clamor of pedestrians, scooters, cars and honking horns, I was distracted by the sight of a bicycle lying inside a large metal container. I stopped immediately. The bicycle was covered by several black plastic garbage bags. Lifting the bags aside, I inspected the machine. My first instinct was that the bicycle had been stolen. But two observations convinced me that this was not the case. First, the tires of the bicycle had the old, cracked, faded appearance of rubber which has not touched the road in years. Moreover, both tires were flat--but not entirely so. It would be one thing to find a single tire in such condition, but to find both tires deflated precisely the same amount, indicated that their present condition was not the fault of shards of glass or errant nails, but simple neglect. Nobody had filled these tires for a long time. Second, the chain and freewheel of the bicycle were covered with a uniform patina of light rust. This was not the sort of deep brown rust which freezes components into fixed shapes, like objects excavated from the earth, but the simple oxidation which accumulates on all steel parts. A quick scan revealed that, as I suspected, the rest of the bicycle did not show weathering equivalent to that of the drivetrain. The aluminum frame was clean. The seat was smooth. The cables gleamed like silver. It was not a bicycle that had been stolen. Rather, it was a bicycle which had been bought, ridden once or twice, and then stored, perhaps in a garage or on a balcony, until the owner eventually recognized that it was only taking up space, and with the resolution of the New Year threw the bicycle into the garbage. A bicycle does not belong in the garbage. I removed the bicycle from the container. I wheeled the bicycle home. I leaned the bicycle against the wall in my apartment. What would I do with the bicycle? It was too small for me to ride. Besides, I already had a bicycle, as did my wife. And none of my friends needed a bicycle. I was late for work. Leaving the bicycle, I exited my apartment, and forgot about the bicycle for the remainder of the day. When I returned home, the bicycle was waiting for me. By then, I had figured out what to do. On the ground floor of my building--another Barcelona tradition--there lives a woman, called a porteria, who acts as a guardian and gatekeeper. The porteria is named Sylvia, a friendly woman who takes our mail when my wife and I travel to the United States, keeps the spare key to our apartment and dutifully records the comings and goings of our guests. Sylvia has a son, named Pedro, fourteen or fifteen years old, at the age when boys grow so fast that you see them one week, and they look like children, and you see them the following week, and they look like young men, filling the space around them with energy. Pedro is polite and cheerful, and I often see him with his friends, usually on his way to play soccer. He walks home from his soccer games, cleated shoes hanging around his neck, scuffed ball under his arm, playing his part in the collective passion of youth worldwide. But he did not have a bicycle. All children need bicycles. As wrote Bernard Hinault, the famous French bicycle racing champion, and five time winner of the Tour de France, "By letting him travel further from home, a bike gives a child a greater sense of space and a new freedom. One's first glimpse of freedom, in fact, is often snatched from a bike. By turning the pedals you can move more quickly towards your most secret dreams." I did not know what Pedro's secret dreams were (probably to become a professional soccer player) but I knew that he needed a bicycle. James E. Starrs, author of The Noiseless Tenor, The Bicycle in Literature, described the universal need of a child for a two-wheeled vehicle: "A childhood without a bicycle is a sailboat becalmed." And so I set about refurbishing the bicycle for Pedro. I pumped up the tires (they held air), and I oiled the chain (the rust disappeared). I went over the bicycle with a set of wrenches, and tightened all the loose nuts and bolts. I adjusted the brakes, and made sure that the gears functioned properly. Finally I raised the saddle to the highest point. The bicycle was the right size, but Pedro was still growing. When the bicycle was finished, it stood ready with a bright, eager quality, as if it was excited to be ridden by an owner who cared. Walking downstairs, I knocked on Sylvia's door, and invited her into my apartment. I showed her the bicycle, and in halting Spanish, explained that I wanted to give the bicycle to Pedro for Los Reyes. At first she did not speak, and then she stood on her tiptoes, and kissed me on both cheeks. Excited plans followed. That weekend, Sylvia and her family were going to her village, which she called, el pueblo. Somehow the bicycle had to be hidden, until it could be revealed on Los Reyes. We stored the bicycle in a closet, and the following day, I helped Sylvia's husband carry the bicycle downstairs, and pack it into their car. The bicycle traveled to el pueblo. On Los Reyes it was given to Pedro. I hope that now he can now travel farther from his home. I hope that now he can find a greater sense of space and freedom. I hope that now his sails fill with wind. Or, simply, I hope that after his soccer games, instead of walking, Pedro can ride home on his bicycle. |

||||||||||||

September, 2006

Les Alpes VaudoisesIn Europe, near the end of the summer, a great migration occurs: people from the northern countries travel south, seeking sun and azure Mediterranean waters, while people from the southern countries travel north, looking for cool climes and calm retreats. Each year, as the exchange takes place, the roads are choked with cars, and the great cities fall silent, the streets deserted, the stores closed, as if the continent were slumbering through a long siesta. In August, Laura and I participated in this holiday ritual. We packed our car in Barcelona and set off for Switzerland. Crossing the border at La Jonquera, we followed the coast past Perpignan, and turned north toward Lyon, where we left the dry rolling country of southern France, and climbed into the foothills surrounding Grenoble. In the evening, we reached Geneva, where we spent the night, before continuing the next morning, through Lausanne, and around the tip of Lac Leman into the Rhone valley. Near Monthey, we turned off the highway and wound into the mountains. Our destination was the town of Gryon, nestled in a small valley, below the Vaud Alps, a region famous for Chablis wines and ski resorts. Soon we arrived at a chalet, rented by one of Laura’s friends, Ivana, who had retreated to the country with her two boys, Clement, age six, and Timeo, age three, leaving her husband in Geneva. Ivana’s invitation and abundant hospitality made our vacation possible. There we passed a long week enjoying the pleasures of the mountains. We strolled through picturesque country that appeared to have been copied from a postcard: green meadows dotted with flowers, large brown and white cows with bells around their necks, farmhouses with wood facades and boxes of red geraniums beneath their windows, snow-covered peaks which stretched to the horizon. We rode a large ski lift, or telecabine, to the top of a peak, where we watched summer crowds skiing on a glacier. We enjoyed meals of fondue and plates of champingnons, accompanied by fruits de bois, fresh raspberries and strawberries, washed down with sureau, herb-flavored water, or rose wine. We took the waters at the Bains de Lavey, a modern thermal spa, replete with open-air pools, showers and baths overlooking the Rhone. Our cultural immersion was so complete, that Laura, who grew up in Geneva, claimed that she had never experienced anything so thoroughly Swiss. On my last day in Gryon, I drove to the nearby town of Villars, rented a mountain bicycle, and rode a sleek red train to the top of a nearby peak. The train climbed a narrow track with a toothed wheel, cutting through forest and meadow, passing several small stations, announcing its presence with a shrill whistle. Eventually, the train arrived at the last stop, the Col de Bretaye. I consulted the map which I bought at the tourist office, and set off on the mountain bicycle. The bicycle which I had rented was a utilitarian model, produced by a prominent American company. It had over-size, welded, aluminum frame, an air-sprung, oil-damped suspension fork, hydraulic disk brakes, and machine-built, minimally-spoked wheels. Adding to its functional character was the fact that the bicycle was completely black, including the rims, tires and cranks, like a piece of machinery. When I left cycling, components like suspension forks and disc brakes were just being introduced, and I was curious to see how they had developed. For all that has been written about modern technology and the loss of traditional values, I have to report that the bicycle performed flawlessly. The suspension absorbed the ups and downs of the trail without absorbing the energy of pedaling, the disk brakes brought me from high speed to a full stop even when covered in mud and water, and the gears changed smoothly and consistently, so much so that I hardly felt the chain moving at all, I simply stabbed the black levers beneath the handlebars, and kept pedaling. The bicycle disappeared beneath me, an extension of my body. Above Villars is a long ridge, oriented east to west, which separates Vaud from the German-speaking portion of Switzerland. I planned to ride along the ridge, from the Col de Bretaye to the Col de la Croix, before returning to the train station by a different route, and descending to Villars. This itinerary, I hoped, would provide good views of the country, and had the added benefit of remaining almost entirely in the sun. American novelist Ernest Hemingway, known as a follower of the Tour de France, commented, “It is by riding a bicycle that you learn the contours of a country best.” While this is certainly true of road cycling, it seems especially true of mountain bicycling. There is a unique balance, between the ability to cover distance and the potential for close observation, which separates mountain bicycling from other forms of transportation, such as walking (too slow) or driving (too fast). On a mountain bicycle, you are forced to adapt to the terrain, while, at the same time, you are brought into direct contact with the earth, the rocks, the flora and fauna, the natural world. My ride began on a wide road which dropped from the train station along the ridge. Soon the road changed to gravel, to dirt, and to singletrack. For the most part, the trail passed through open meadow, however, intermittently, the trail entered forests of pine and spruce, larch and fir, beach and maple. Every few kilometers were small gates, which marked the boundaries between pastures, and frequent metal posts with yellow signs pointed toward other trails and towns. And of course there were mountains. Directly ahead was Les Diablerets, dusted with snow, a cool blue glacier visible near the summit. To the east was the rough block of the Grand Muvern, circumscribed by trails, while to the south were the Dents du Midi and Mont Blanc, lofty white peaks standing against the blue sky, appearing and disappearing in clouds. Riding through the alpine country, I felt something inside me open, and I pushed myself harder. It had been a long time since I rode like that, driving the pedals on the uphills, tucking low and swooping down the descents, standing and sprinting up the steep hills. As I crested each hill, greeted by breathtaking views, I decided that the Alps were the perfect place to ride mountain bicycles. Switzerland is not the country where mountain bicycles were invented, but the Alps are the range where our modern relationship to mountains evolved. “Three centuries ago,” wrote Robert Macfarlane, author of the intriguing Mountains of the Mind, “mountains were particularly repellent landscape forms: it was felt that their irregular and gargantuan outline upset the natural spirit-level of the human mind.” During the Eighteenth century, a combination of factors precipitated a change in the way people perceived mountains. Romantic sensibilities, colonialist greed, and the growing need of industrialized society for natural places, transformed mountains into symbols of wilderness and majesty. This process culminated in 1786, with the historic first ascent of Mont Blanc. We participate in this legacy every time we ride mountain bicycles. I learned these facts while conducting research for a long project about mountains and mountain climbing, the sport which captured my imagination after bicycling. But I find myself returning, over and over, to the bicycle. Perhaps this is because on days such as that in the Vaud Alps, wearing baggy shorts and a T-shirt, map tucked into my waistband, wind blowing through my hair, I feel alive. As said Eddy Merkx, the most famous bicycle racer of all time, “On a bicycle I was simply myself.” Eventually I reached the Col de la Croix. The rough vibration of the trail was replaced by the smooth rush of pavement, before I turned back onto dirt, and climbed steeply to Ensex, a small farming community below the ridge. The fields were light green tinged with brown, and the farmers were taking in the hay. In the meadows the Edelweiss was no longer blooming, and the slopes were covered in brilliant purple spears of lupine. It was late summer, and the tourist season was almost over. From Ensex, I rode back to the Col de Bretaye, passing through stands of dark green trees, where golden threads of spider webs stretched across the trail, emerging back into bright sun. When I reached the train station, I followed the signs toward Villars. The trail ran along the tracks, and then cut into the forest, and plunged down a series of tight switchbacks, steep flights of stairs, and narrow bridges, built from felled logs. The trees filtered the light from above, and the undergrowth was dark and moist. Small streams ran through the black soil, and the logs were covered in thick green moss. Through this magical world I descended, easing around the corners, rolling across the bridges, carrying the bicycle over the most difficult sections. Finally, I came out above Villars, and coasted down to the town, thrilled by the descent, and stunned by the beauty of the forest. The day affirmed my belief that the Alps are the perfect place to ride mountain bicycles. Therefore, if you visit Europe, perhaps to follow the Tour de France, ride the famous climbs such as L’Alpe d’Huez, sample the fondue and the Chablis, rent a chalet for the month of August, but, by all means, bring your mountain bicycle, and ride in the Alps. You will not be sorry that you did. |

||||||||||||

Basic Black BikeThere was a time when I identified people based on the bicycles they rode. I was working as a mechanic in a bicycle shop in California, and sometimes it was easier to remember customers? bicycles than their names. There was the man with the white Cannonade who rode religiously every day. The man with the Raleigh three-speed who was a jazz musician. The man with the Italian frame who drove a taxi in San Francisco. Anybody trying to characterize me in a similar fashion would have been hard-pressed to find a bicycle which matched my habits: I had a racing bicycle, a track bicycle, a touring bicycle, a mountain bicycle, a city bicycle, and various other bicycles which blurred the boundaries between these categories. My identity was simple: I was a bike guy. I worked in a bicycle shop, raced on the weekends, bought French magazines to follow the professional season in Europe, shaved my legs and indulged various other rituals of the obsessed. Now all those bicycles are gone. I saved just one bicycle, an elegant road machine which I brought to Europe when my wife and I moved to Spain. After one year of living in Barcelona, the bicycle was destroyed by the errant bumper of a car, and I was bicycle-less for the first time in almost two decades. Miraculously, life went on. I accustomed myself to the bi-pedal instead of the bi-cyclic, and the world of bicycle racing faded in my memory. I loosely followed the professional season, more from habit than passion, and even went to see a few local races, but, for the most part, I ceased to be a bike guy. City life soon demanded that I look once more to the bicycle. A new job meant that I worked on one side of the city and lived on the other. Driving a car to and from work was wasteful and environmentally unsound, and public transportation was tedious and expensive. Thus the bicycle. I faced a question: What bicycle did I want to bring into my life? Another way to phrase this question: Who was I? Two contrasting bicycles presented themselves. The first was a modern mountain bicycle from the United States. The mountain bicycle had a bright red frame festooned with flashy stickers, a massive black suspension fork for downhill racing, disc brakes and wide handlebars which encouraged leaping and jumping. Overall, the bicycle had an aggressive and industrial feel, like an off-road motorcycle. A quick spin around the block convinced me that it would suffice to get me to and from work. But did I want a modern mountain bicycle? The second bicycle was produced by a small shop in an alternative neighborhood known as El Born. The shop was on a small square, beside a café, surrounded by Roman walls. With a basic black frame, fenders, chaingaurd, bell and upright handlebars, the bicycle had a practical yet stylish European aesthetic, like a classic Vespa scooter. It was the perfect solution for urban transportation. I bought the second bicycle. Now that I have a bicycle again, I think about the world of racing more often. I frequently log onto the web for race results, I have favorite riders, and I plan my summer vacations around the annual arrival of the Vuelta de Espana near Barcelona. Sometimes, as I ride around the city, I drive the pedals and push myself harder, wind blowing through my hair, body falling into the old rhythm. Bicycle racing is a part of me. But in my neighborhood, to the young bike guys who pass me on their racing bicycles, on their way to Montjuich park to race, I am simply the man with the basic black bike. |

||||||||||||

June 2006

Cap ProblemaIn Barcelona there is a unique bicycle shop called Cap Problema, which means, “no problem” in Catalan. The shop is on a small, quiet square (perfect for test riding bicycles) in the old part of the city, surrounded by Roman walls. Next to the shop are several cafes, and a second bicycle shop which specializes in renting bicycles to tourists. Cap Problema does a great deal of business selling Bromton folding bicycles, which are very popular in Barcelona. The store also produces its own city bikes. The frames are made in Taiwan, and the parts are assembled from various suppliers, including Brooks (saddles) and Schwalbe (tires). The model of these city bikes is called Miliano, after the owner and visionary who created the shop, Dany Miliano. My wife and I recently bought matching Miliano bicycles to ride around Barcelona. The bicycles are very practical, with upright positions and fenders, as well as being nimble and light. Dany was intrigued to learn about Jitensha Studio, and the small silver bells you can see on our were inspired by the Jitensha Studio web site. Dany supports city bikes as a form of transportation in many ways, including helping to organize a yearly bike to work day. He also restores antique bicycles, including a very interesting three-wheeled utility bicycle from the early part of the century. Other interesting details from the shop include an air compressor mounted below floor level and covered in a sheet of glass, and repair stands which descend from the ceiling on electric pulleys (floor space is very limited!). If you visit Barcelona, be sure to check out Cap Problema, or check out the shop on the web at www.capproblema.com. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| September 2005

A Tale of Two Bicycles Weekends, Laura and I often travel to the town of Llanca, on the Costa Brava, two hours north of Barcelona. Many of the towns along the Costa Brava have become so populated with French, German and English tourists, and so crowded with summer rentals and hotels that they resemble holiday theme parks, however, Llanca has retained some degree of its charm, with a pleasant old town, several churches and a small, lively port with a functioning fishing fleet. Development is limited, and nearby there are pleasant beaches, small protected coves and the Cap de Creus natural park. In the port, Laura’s parents owns a small apartment, which they use as a summer retreat, and a layover during long drives between Switzerland, their adopted home, and Spain, their native country. The apartment is crowded with objects accumulated over many years: collections of sea shells, paintings of fishing boats, folded beach towels, empty bottles of sunscreen. In the basement, between dusty windsurfing boards and deflated beach toys, are two bicycles. The first bicycle is relatively modern, a mountain bicycle, made in Italy, in the 90’s. The bicycle has a ladies frame, with oversize steel tubing and a unicrown fork, painted bright metallic blue. The components include imitation twist-grip shift levers, and anonymous SIS derailleurs, which move the chain over sixteen speeds. The only features which distinguish the bicycle from thousands of similar machines sold in the United States, are fenders, front and rear lights, generator and a small luggage rack. On the downtube are the following words, lost in translation from Italian to English, “Country Tourney Jumper.” The second bicycle is much older, a three speed, made in Geneva, in the 60’s. The bicycle also has a ladies frame, with slender tubes and scalloped lugs, painted silver. Some of the components are familiar, such as the cottered cranks, while others are unique, such as the fancy chain guard. Like the first bicycle, the second bicycle wears fenders, front and rear lights, generator and rear rack. On the chrome plated handlebars is engraved the name, “Tissot,” perhaps related to the famous Swiss watch company, while the headtube bears a tin headbadge, and the words, “Cycle Sporting.” These two bicycles reflect changes in production during the last century. Since World War Two, durability and serviceability have been surmounted by cost-savings and marketability. Hand-painted lugs have disappeared, leather saddles have been replaced by foam saddles, and aluminum components have been exchanged for plastic components. Such changes are common to many industries, and suggest greater and more important changes in the world. Also, despite the fact that these two bicycles are apparently so different, they are designed for the same purpose. That purpose is to be purchased by families and other non-serious riders, piloted around cities carrying shopping bags and groceries, and stored in basements and hallways waiting for weekend spins in the park. This is how Laura and I use the bicycles in Llanca. Mornings, I roll the mountain bicycle out of the garage, and pedal to the port, stopping to wait for the newspaper stand to open, and picking up fresh bread from the bakery on the way back. Afternoons, Laura and I ride to the old town, and sit on the terrace of the cafe, watching elderly people emerge from the siesta, as teenagers roar past on motor scooters. Even though the bicycles are too small, we sometimes venture farther, to La Farella, a small sheltered beach perfect when the wind is blowing down from France, or to Azucenas, another beach on the far side of the headlands, where we push the bicycles through wild pine woods on twisting brown paths, which Laura knows from many summers. Thus, we ride the bicycles through Laura’s past, her childhood and her adolescence. And we ride the bicycles through our present, which we are creating in Europe together. And we ride the bicycles into our future, pedaling and talking about where we want to live, what country we want to call home. Quite simply, we dream. Such is the ultimate purpose of bicycles. |

||||||||||||